Kimhi’s Thinking and Being – Chapter 1 – (Sections 1 and 2)

The first chapter of Kimhi’s book (The Life of P) begins to outline why Kimhi thinks there is a form of thinking logic that is neither purely logical nor purely psychological nor operating between a hard divide between those aspects.

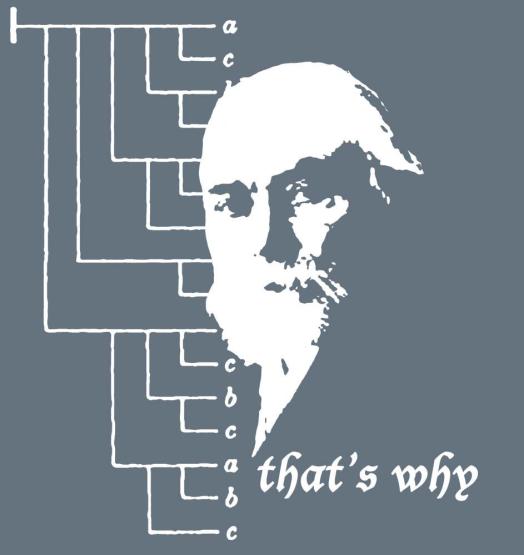

He begins to do this by analyzing how the law or principle of contradiction has typically been thought in two difference ways: ontologically (OPNC) and psychologically (PPNC). In the first case (OPNC) and following Aristotle something cannot both hold good and not hold good of the same thing (25-26). For Aristotle something cannot both exist and not-exist and this is important, Kimhi emphasizes, because it compromises the bottom rung of philosophical generality – a generality which allows philosophy to be the study of being qua being (26-27). This generality, still following Aristotle, means that being is beyond or more than nature and hence philosophy is not a special science but investigates those principles which ground all special sciences (even though those sciences do not investigate said principles).

[It is worth noting that here Kimhi seems close to Meillassoux in that non-contradiction appears to be the only thing that cannot be thrown out even after a total rejection of metaphysics in its classical or dogmatic sense).]

How Kimhi cashes this out is not presented in an altogether clear manner since if philosophy is the discourse of being qua being principles of reasoning apply to intellects as principles of thinking while principles of reasoning applied to natural substances are principles of being (27). In this sense the OPNC applies to nature while PPNC applies to thought but there is also thought which is not predicative hence with the generalized principle of non-contradiction (that is, in both forms) applies to thinkers (beings like us).

Kimhi is not explicit about how he makes his next move (though it becomes more obvious retroactively) but the assertion seems to be that this split and yet the fact there seems to be a third place or a hinge between the ontological and the psychological is what necessitates a third way of understanding the principle, i.e., of making its generality nameable in some more ‘rigorous sense’ namely as a logical princple. The division of the PNC as ontological, logical, and psychological is something that has become common especially in understanding Aristotle and a division which is radicalized (though more in a Platonic vein) in Frege 28-29). Kimhi cashes this out but not till p. 35.

Following all of this Kimhi then gives the first direct account of what his position is relative to the ontological, logical and psychological. On p. 30 He identities four positions:

- Psycho-logicism

- Logo-psychism

- Psycho/logical dualism

- Psycho/logical monism

On the following page (31) Kimhi gives very brief descriptions of the first two positions, a longer description of the third position (which is the ‘classical’ understanding of Frege) and the fourth is the position Kimhi wishes to advance throughout the rest of the text. These positions are all articulated in relation to how they treat the PNC. Psycho-logicism treats the OPNC as a projection of the PPNC whereas Logo-Psychism is the opposite move. Since no names are named in this section it is difficult to know who Kimhi means exactly… For the Third position he seems to have Frege in mind when he writes that a third form is added (that of the logical) that has kind of a normative weight – in that you should not make contradictory statements. Much of the rest of Section 2 (another 20 pages or so) is dedicated to how this third position arises, particularly in Frege, as a response to the first two forms. But, before moving on to this, Kimhi outlines his own position which is number 4 above (Psycho/logical monism).

Kimhi’s position takes beliefs, judgments, or thoughts (which are all the same at the level of reality to which they refer) to be an immanent unity that only makes sense depending upon where it is placed relative to other unities. A propositional sign displays an act of consciousness but the identity of this mental act depends upon its location in the levels of unities. Thus, for Kimhi, the statement (P and ~P) is not an act of consciousness on its own terms (as a statement of logic) but this is not because OPNC is correct but because ‘I think’ and ‘I believe’ are different types of acts in the same monistic structure.

Kimhi is not altogether clear on this page though it is presented as somewhat prefatory. Instead of further articulating what this monism means (which is done in Section 3 of Chapter 2) Kimhi wants to show how the usual way of reading Frege, and also using Frege to read Aristotle, also views types of logical thinking as different types of mental acts. Psycho-logical dualism attempts to avoid the first two positions above by neither ignoring the subjective act nor the objectivity of propositional content (33-34). According to Kimhi Frege does this by advocating a functionalist approach where logic can give us some objective identity of the statements (mapped out in the scheme of the Begriffschrift) while also maintaining the subjectivity of the act of thought by tracing the appropriate functions given the context.

Kimhi takes issue with Frege’s approach as ignoring the deeper unity which allows the reference/sense (as modified object/subject or extension/intension) to get going in the first place. He attempts to fudge this by added the laws of thought as third mediator between the laws of truth (which corresponds to the OPNC) and the laws of holding true (which correspond to the PPNC) (33-34). Thus the laws of thought hold together the generalities made by signs on the one hand and generalizations of empirical psychology on the other hand. Kimhi will go on to call the laws of thought NPNC or the Normative Principle of Non-Contradiction (36).

Kimhi continues to demonstrate the need for his type of monism by showing how similar structure is essentially smuggled into accounts of the purported dualism of judging and believing. So if judgment is about saying yes or no (this or that is or is not the case) it is difficult, in the case of Descartes for example, to show how willing and judging can be properly separated yet also work in concert (37). Against this Frege can be seen as endorsing (following Peter Geach) the point that something can be asserted and denied and yet still recognized as the same proposition. The cost of this is that assertoric force must be separated completely from the content of a proposition in order to maintain the functionalist picture that Frege desires. Kimhi wants to argue that removed from its functionalist requirements this point becomes essentially that of Wittgenstein and the maximal context principle (that actual occurrences of the proposition give you the map of its meaning and not any schema a la the begriffschrift.

[Again, a note, as Matt pointed out Frege can be read as having an expanded form of the context principle if the begriffschrift is understood in the terms suggested for instance by Danielle Macbeth. Kimhi reads the stroke of the begriffschrift as extra-functionalist in a way that disrupts the whole endeavor whereas, as far as I understand Frege following Macbeth, the marks of the begriffschrift should be read more extensionalist in a non-functionalist sense in that the map of predicates requires levels of artificiality which in itself moves the boundary of the predicative.]

Here the stakes of Kimhi’s monism peek out again – the sense of a beyond or a limit beyond limits should be understood as syncategorematic (as not functionally embedable). For Kimhi assertions cannot be contained in written language according to its logic – assertoric force cannot be ‘there’ on the page it can only be displayed (or gestured to) (43-44).

Kimhi argues that Frege betrays his three commitments in The Foundations of Arithmetic and that Kimhi then in turn transforms these commitments into monsitic rather than dualistic principles:

- Separate the psychological from the logical

- Meaning only exists in propositional contexts

- Keep in mind the distinction between concept and object

Kimhi states that is syn/categorematic distinction is built on 1, syncategorematic unity of a propsition is a version of 2, and that singular term/verb difference internal to the predicate is a version of 3. I do not have the Fregean capacity to analyze how much Kimhi’s reading of Frege is based on a selectively and historically limited treatment of Frege or whether the point about functionally extensionality is as problematic as he argues.

Kimhi ends by stating that neither Frege nor Russell can articulate the distinction between asserted and unasserted without violating an aspect of their own system (or without wandering dangerously close to psychologism of some kind). Kimhi then closes the chapter by claiming that what Wittgenstein means by psychological is psychological in the monistic sense that Kimhi is defending, that is, syncategorematic as something part of but not expressed by the symbol. Kimhi ends with by arguing that Wittgenstein moves from a weak dualism to a deeper understanding of his own monism, that the agreement between judgments is as logical as the agreements of measure – thus the assertoric force of measure is based upon a logic and can only be then shared logically but its force as an actual instance is not the same as the rules applied to either side (51).

Filed under: history, ontology | Leave a Comment

Tags: analytic continental divide, begriffschrift, contradiction, Frege, irad kimhi, Meillassoux, noncontradiction, WIttgenstein

No Responses Yet to “Kimhi’s Thinking and Being – Chapter 1 – (Sections 1 and 2)”